Brown, Father Raymond E., S.S.

1998, August 8

Date of Birth: 1928, May 22

Passionist Father Donald Senior, CP, was tasked by the Society of St. Sulpice to create a biography of this iconic Sulpician scholar. Fr. Senior’s work resulted in his 2018 publication Raymond E. Brown and the Catholic Biblical Renewal published by Paulist Press. Fr. Senior recently gave an interview reflecting on his biography of Fr. Brown and his personal memories of this faithful Sulpician.

View the news item and link to the video interview here.

SCHOLAR AND TEACHER

The sudden and unexpected death of Raymond E. Brown brought to an end more than forty years of biblical study, beginning with his 1955 doctoral thesis on the sensus plenior (S.T.D., St. Mary’s Seminary) and ending with his magisterial Introduction to the New Testament (1997).

Before reviewing Ray’s life and achievements, a few words about the twentieth-century church context in which he did his work may be helpful. The century did not begin well for theological scholarship in the church; the early decades of the twentieth century brought to the fore reactionary integrism, promoted by the even active persecution of scholars and teachers. Only in 1943, with the issuing of Pius XII’s encyclical on biblical studies (Divino Afflante Spiritu) did the assault on biblical scholarship begin to come to an end. And it was only ten years later that Ray was ordained and began his study of the New Testament. Ray’s NT work was only possible in the new era opened by this official change of position in the church effected by one of the great Popes of this century.

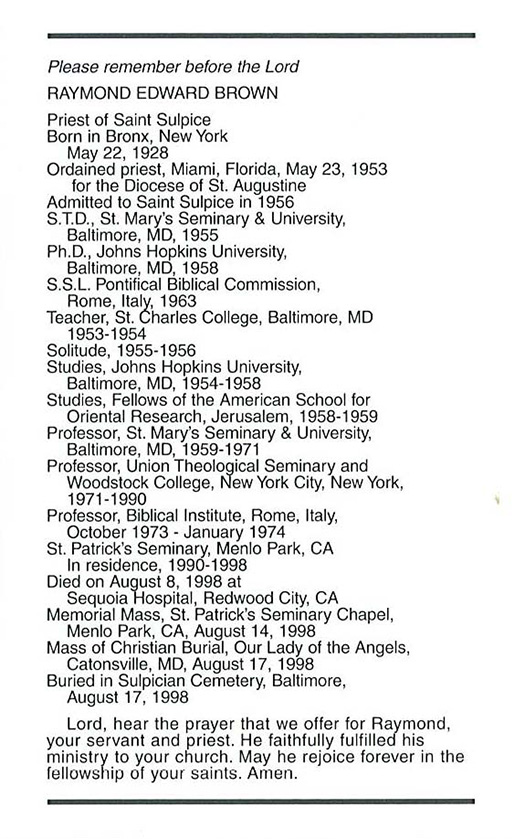

Ray was born in New York City on May 22, 1928. The move by the family to Florida in 1944 brought Ray to the diocese of St. Augustine, where he was ordained to the priesthood in 1953. Pre-ordination studies (1945-53) were done at St. Charles Seminary College, and his theological studies at the Catholic University of America, the Gregorian University in Rome, and St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore. After ordination and a year of high school teaching at St. Charles College, he began doctoral studies at the Johns Hopkins University under the foremost Orientalist of the century, W.F. Albright. Like Joseph Fitzmyer, his fellow Hopkins student and longtime friend, Ray moved naturally from ancient Near Eastern studies to the study of the New Testament – a career path different from that normally taken by students of the NT. Ray’s linguistic and historical work at Hopkins gave him entrée to the new world opened up in biblical scholarship by the Dead Sea Scrolls; his 1958 doctoral dissertation at Hopkins (The Semitic Background of the Term “Mystery” in the New Testament, published in 1968) shows already the impact the Scrolls were to have on his biblical work. In 1958-59 he was given the opportunity of working on the Scrolls in Jerusalem, before he began his twelve-year tenure as professor of New Testament at St. Mary’s, after admission to the Society of St. Sulpice in 1956. In 1971, he accepted a joint professorship at Woodstock College, a Jesuit theologate that had recently moved to New York, and at Union Theological Seminary. After Woodstock’s closing, he became professor of New Testament at Union, ending his career there in 1990 as Auburn Distinguished Professor of Biblical Studies.

After retiring from Union in 1990, he was invited by Archbishop John R. Quinn of San Francisco to take up residence at St. Patrick’s Seminary, in Menlo Park, CA. His relatively early retirement from Union at 62 was meant to provide him the time for several important projects; and in the eight years there before his death, he produced a second, expanded edition of The Birth of the Messiah (1993), completed his two-volume study of the canonical Passion narratives, The Death of the Messiah, in 1994, and published his last major work, The Introduction to the New Testament, in 1997.

I first met Ray in 1953, the year he spent at St. Charles, teaching high school students English, history, and science. More significantly, I met him again at St. Mary’s, when I began theological and biblical studies in 1961. It was in those years that I became a reader for Ray, checking his manuscripts for typos, inelegancies, and the like. I later “graduated” to the position of his Sulpician censor, after ordination and graduate studies. By the time of his death in 1998, I had known Ray for some forty-five years, as teacher, as colleague, and as friend.

Rather than attempt a summary of his fruitful and prolific career, which will be covered in a more extensive biography, I would rather focus on several aspects of his life as priest and scholar. [The memorial card contains the major dates of his Sulpician assignments.] First of all, he lived out his Sulpician vocation of clergy formation in a thirty-year career of teaching seminarians at St. Mary’s and at Union Seminary. A generation of Catholic and non-Catholic seminarians, ministers, and priests was guided by Ray through the historical and theological interpretation of the New Testament, and its vital importance in the life of the church.

Ray’s teaching went beyond the classrooms of St. Mary’s and Union. A popular lecturer on the New Testament, he estimated that he gave more than a thousand lectures, workshops, programs, and the like, introducing post-Vatican II Catholics and others to the riches of the Bible. He was also committed to training and encouraging the next generation of biblical scholars, to carry on the work. His Sulpician students, like John Kselman and Michael Barré, and his doctoral students at Union (like Marion Soards, who read one of the lessons at his funeral) form an important part of his legacy.

Ray taught as well by his many books and articles. His lifelong fascination with and love of the Fourth Gospel bore fruit in his commentaries on the Johannine Gospel and Letters, and in his reconstruction of the Johannine church, in The Community of the Beloved Disciple (1979). This last book was one of a trilogy on the early church, including Antioch and Rome (co-authored with John Meier, 1983) and The Churches the Apostles Left Behind (1984). One of his final works, A Retreat with John the Evangelist (1998), which appeared only a day or two before his death, is perhaps his most poetic and whimsical treatment of John’s Gospel. Yet is shows Ray’s ceaseless attraction to that Gospel and the community that lies behind it.

Ray’s work as an ecumenist deserves comment. In 1963 he became the first Roman Catholic to address the Faith and Order conference of the World Council of Churches; later, by agreement between the Vatican and the WCC, he served for twenty-five years (1968-1993) as the only American Catholic member of the Faith and Order Commission. He was as well a long-serving member of the Lutheran-Roman Catholic dialogue; out of this dialogue came two noteworthy monographs on sensitive ecumenical topics, Mary and Peter, both edited by Ray. (One wonders if it was Ray’s exposure in early adulthood to men and women of other faiths at Johns Hopkins University, and in his time in the American Schools of Oriental Research in Jerusalem, that awakened his interest and commitment to ecumenism.) More could be said of Ray’s life – of the honors he received (more than twenty-five honorary doctorates from universities all over the world); of his work for the U.S. bishops, interpreting for them the impact of biblical studies on church thinking and teaching; of his work for the whole church as a member of the Pontifical Biblical Commission 1972-1978; and from 1997 to his death. But let me conclude rather with a few reflections on Ray’s understanding and living out of his Sulpician vocation, which included both his ordination to ministerial priesthood and his commitment to biblical scholarship. In this era of the “hyphenated priest,” he never felt any inconsistency or conflict between the two roles of priest and biblical scholar and teacher. As he pointed out in an early book (Priest and Bishop), one of the responsibilities of the Old Testament priesthood was the office of teacher. And Ray’s dual vocation of priest and teacher was unified by a single virtue, the virtue of fidelity: fidelity to the church as a priest, and fidelity to the sacred text as a scholar.

Ray was both a realist and an optimist in his fidelity to the church. He realized that it was a human church, indeed a “church of sinners,” as Karl Rahner put it; and he knew that, within his own area of study, there had been grave injustices done to theologians and scholars in the history of the modern church; but he saw in his own lifetime the church change direction in a far-reaching way, from persecution to toleration of theological scholarship, and even to the beginnings of the influence on church teaching of such scholarship. One can understand how painful it was to him when he was attacked as disloyal to the church and its teaching. The support of the institution’s leaders, bishops and Popes, gave the lie to such an absurdity.

His scholarly life was also a testament to fidelity, fidelity to the biblical text. His use of the method of historical criticism was simply a means to determine what the original authors had intended to communicate to their original audiences. While other methods and approaches were valued by him (for instance, feminist and canonical readings of the text), he believed that the starting-point of good interpretation, faithful to the text, must be the interplay between first-century author and audience.

Fidelity, faithful following and discipleship marked Ray Brown’s life and work. And as he knew so well, fidelity is a rich biblical concept, referring primarily to the fidelity, the trustworthiness of God to His promises and His people. Ray, a faithful servant, put his trust in the utterly reliable promise of God to be with his people in life and in death.

On August 14, 1998 a memorial Mass was celebrated in the chapel of St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park where he had lived for the previous eight years. Archbishop William J. Levada, the archbishop of San Francisco, was the principal concelebrant, and the provincial, Fr. Ronald D. Witherup, preached the homily. Cardinal Roger Mahony was in attendance, and many bishops and more than one hundred and fifty priests concelebrated the Mass.

The body was returned to Maryland for the final Mass of the Resurrection which was celebrated in Our Lady of the Angels Parish, the site of the former chapel of St. Charles Seminary College where Ray had begun his teaching career more than forty years before. The principal concelebrant was Cardinal William H. Keeler, Archbishop of Baltimore, accompanied by Cardinal Bernard F. Law of Boston, Fr. Lawrence B. Terrien, Superior General of the Society of St. Sulpice, and several other bishops and some one hundred priests, including many of Ray’s Sulpician colleagues. The provincial, Fr. Ronald D. Witherup, delivered a final homily, a slightly revised version of the one given at Menlo Park. Many out of town guests were present, including Ray’s surviving brother, Robert, his wife Irene, and their son Robert, along with several relatives, colleagues from Union Theological Seminary in New York, and friends. Ray was laid to rest in the Sulpician cemetery alongside the confreres who had preceded him in death.

Let me close these reflections with the words of a great Anglican interpreter of Ray’s beloved Gospel of John. Commenting on John 12:26 (“Whoever serves me must follow me; and where I am there also shall my servant be”), Archbishop Temple wrote: “Follow me; this is the whole of a Christian’s duty; and where I am there also shall my servant be: that is the whole of a Christian’s reward.” May Ray rest from his labors now, in the eternal peace and joy of God’s kingdom; and may those who mourn him be comforted by their conviction that in life and in death he entrusted himself to a loving and faithful God.