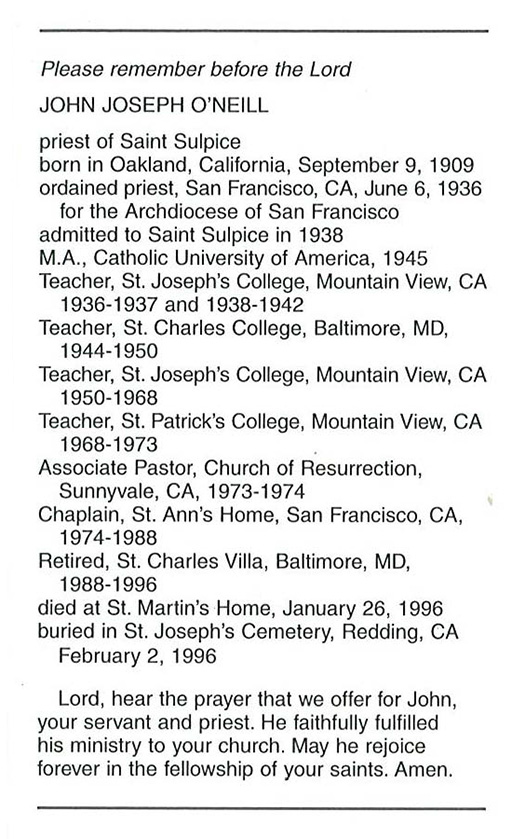

O’Neill, Father John Joseph, S.S.

1996, January 26

Date of Birth – 1909, September 9

March 19, 1996

In the Sulpician Archives at Catonsville is a nine-page document entitled “The College Religion Course,” intended for the proposed union of the college departments of St. Joseph’s College at Mountain View and St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park. Dated June 1966, it gives in outline form the rationale for the program, the areas to be covered in each of the eight semesters, a bibliography, and even the relationship of the course of religion to other areas of study. It is signed by Rev. John J. O’Neill, S.S., then at the halfway point of his priestly career, an earthly life that came to an end on January 26, 1996. The document is one of many that he left behind to express the continual concern and even zeal for things spiritual and things educational that marked almost all of his eighty-six years on this earth.

John Joseph O’Neill was born in Oakland, California, on September 9, 1909, a date he always noted as 9/9/09. His parents were Thomas F. O’Neill and Bridget O’Neill (her maiden name as well as her married one). Though he was able to get his elementary education at Sacred Heart School in Oakland, his mother died when he was only eleven. His father could not cope with the loss, and John spent several years in foster homes, separated from the rest of his family. The only one he was close to was his sister Mary. After her marriage, her home in Redding, California, became the one home he knew in later life. He also had a younger brother whom he got to know only when James entered the seminary to study for the priesthood. Though his brother was ordained in 1941 and served with distinction as a priest of San Francisco, as a military chaplain, and later in the Diocese of Oakland, John suffered a great loss when his brother left priestly ministry and was married.

When in 1924 St. Joseph’s College was separated from its previous location at St. Patrick’s Seminary and opened at Mountain View, John O’Neill enrolled in the first freshman class there. He spent six years in the minor seminary under the tutelage of the new President, Father John J. Jepson, S.S., and the other pioneer members of the faculty: Fathers Francis Kunkel, Benjamin Marcetteau, Alexander Peltier, Victor Bast, Edward Aycock, and, of course, Eugene Saupin, who arrived in California when John was entering the third high class. The young seminarian would later write of those days when he did an article for the Borromean of St. Charles College on the occasion of the silver jubilee of St. Joseph’s in l 949. After graduation in June 1930 John went on to St. Patrick’s, Menlo Park. Though we do not know many details of his major seminary career, he entered just after the death of the long-time first rector, Father Henri A. Ayrinhac, S.S., and so he spent his six years at St. Patrick’s under the direction of Father John J. Lardner, S.S., who would later serve as U.S. Provincial. Among John’s fellow students was one James A. Laubacher, who was ordained priest just as John was finishing philosophy. Whatever happened between 1930 and l936, the idea of a Sulpician vocation developed along with his priestly preparation. John was ordained by Archbishop John J. Mitty on June 6, 1936, at the old St. Mary’s Cathedral in San Francisco.

In his first assignment the new priest returned to St. Joseph’s for the year 1936-37 to teach Greek and (under the tutelage of one of his confreres) physics. After that one year he was sent to Baltimore to make his Solitude under one of his old teachers, Father Marcetteau, and the Socius, Father William Dwyer.

With the completion of his year of novitiate, the new Sulpician went back to St. Joseph’s for another four years, this time teaching science, Greek, English, and elocution and serving also as Infirmarian. During this time, he began to spend some of his summers taking courses at nearby colleges and universities, especially to fill in gaps in his knowledge of the classes he was assigned to. This prompted on the part of his superiors the question of graduate studies because he had only a bachelor’s degree from the seminary.

It wasn’t until the fall of 1942 that the Provincial Council freed Father O’Neill to come to The Catholic University of America to work for his master’s degree. Father Fenlon had asked him earlier what subject he wanted to study, whether science or English or history. In the end he chose Modern European history, and he came to Washington to live at Theological College, not in the crowded main building but in the Casa on Fourth Street. It may have been his first time on his own or the distance from where he had lived and worked, but for his first months at the University he fell into a kind of depression —perhaps a delayed reaction or trauma from his childhood losses and uprooting. Whatever it was, he seems to have recovered by the end of the semester, and he was able to pursue his courses in history as well as some allied studies to fit him for the variety of classes he had already taught or would be assigned to in the future. His master’s thesis examined the Roman Question, and he later reported that he found time in wartime Washington to go on Sundays to the White House to offer Mass there for the large number of Catholic servicemen among those assigned to guard the President. Though he never would go on for a doctorate, summer school courses to update himself in Scripture and theology would be a frequent part of his life into the late 1960s.

With an M.A. to put after his name, Father O’Neill was assigned in 1944 to St. Charles College in Catonsville. There for seven years he taught classes in Latin, history, science, and religion. Maybe it was the wide variety of subjects he taught or some other cause, but he soon got to be known for his absentmindedness. He would not infrequently go to a classroom, give back test papers or assignments, and then discover that he was in the wrong classroom. In spite of that, he became concerned about the running of the house, because he felt that the superior should work in a more collegial way. John would cite chapter and verse of the Sulpician Constitutions to bolster his viewpoint. By the same token he became very much involved in a work that was just beginning, that of putting together a syllabus in each subject that would promote more consistent results in the teaching of the various disciplines.

Before he and the different committees could make much headway, John O’Neill was transferred back to Mountain View in 1951. There for a stretch of seventeen years he taught Latin, Greek, history, religion, and social studies. Once again, his reputation for being absentminded grew and increased. He was known for coming to class, praying the Sub Tuum instead of the Veni Sancte Spiritus, and walking out as if the class had ended. Or, on at least one occasion, he borrowed a house car to go shopping, got what he wanted, and then met friends who offered to bring him back to the College. On his return he put the keys back where they belonged but unknowingly left the car at the shopping center for several days. Perhaps the most famous incident occurred when he picked up a set of car keys, went to the garage and opened the garage door, discovered that he was in the wrong car, switched to the other car next to it, and backed through the closed garage door on that side.

But there were so many things to compensate for these lapses. One of John’s special assignments was to be moderator of the house Mission Society. Here he filled a tremendous niche. On the testimony of Father Gerald Brown, S.S., a student in Father O’Neill’s time, he shared with the members of the community an enormous appreciation and love for the missions and for missionaries. His enthusiasm inspired a number to pursue a vocation to Maryknoll or one of the other missionary societies, not only among the Maryknoll minor seminarians who took their classes at St. Joseph’s but among the diocesan seminarians in the house as well. Until 1970 he never had the opportunity to visit the missions, but that summer he traveled around Guatemala with some priest companions. For long years he made sizable monetary contributions to the missions through the Society for the Propagation of the Faith. It should be noted that a June 1987 article in the Maryknoll Magazine paid tribute to the Sulpicians in general and to Father John O’Neill in particular—as another example of mission zeal dating back to the days of Father Joe Bruneau or even earlier.

Another of John’s responsibilities was to serve as faculty secretary. We have a number of examples of his painstaking care in reporting on deliberations and talks in faculty meetings; a case in point is the detailed recounting of Father McDonald’s summing up of achievements and problems during his Provincial Visitation of 1964-1965.

Going along with this ability was his continued interest in the drawing up of syllabi for the various courses. He was soon put in charge of the committee to develop such guides for each of the subject areas. He had some success in Latin and English, as recorded in his frequent letters to the Provincial, but the atmosphere in and out of seminaries of that time did not lend itself to long-term accomplishments.

A further part of his task at St. Joseph’s was to serve as Spiritual Director. His desire for greater involvement in the spiritual life led him to undertake a retreat for the Sisters of St. Joseph of Carondelet in the summer of 1957. He gave the retreat for his fellow Sulpicians in 1963, in June for those in the East and in August for those in the West. A year later he was called to Spokane to lead the diocesan priests there in their annual retreat. The paper on the Proposed College Religion Course dates from this period as well.

Father O’Neill was quite upset in the latter part of the 1960s with the turning over of the high school seminary to the archdiocese and with the effort to combine the two parts of the college on the Mountain View campus. Once again, he felt that the College administration was not sufficiently involving the faculty in decisions. But he still taught theology and history at St. Patrick’s College from 1968 to 1973 and continued as faculty secretary. Then horrified at what he regarded as the “defection” of one of the Presidents from the priesthood, he began drifting away from seminary life. In 1972 he moved to the Church of the Resurrection in Sunnyvale, though he continued teaching classes at Mountain View for one more year. He became a full-time associate at the parish in 1973, but the pastor proved so difficult that he drove away the other associate. So at 64 John O’Neill turned to another ministry.

In January of 1974 he was invited to become chaplain of St. Anne’s Home in San Francisco, where he would work with Mother Jeanne, who had earlier been involved in Baltimore with the arrangements for the staffing of St. Charles Villa. It was the start of fourteen years of faithful ministering to the Little Sisters and the residents of St. Anne’s, even during the rebuilding of the original Home. He also worked with several retired diocesan priests and assisted Father Lyman Fenn in his final year at the Home. The position gave him the opportunity to make visits to his sister’s in Redding and to get to know his nieces and nephews, especially Molly and Colette. It was another great loss for him when Mrs. Mary Steffens, his sister, died just before Christmas in 1983.

Father O’Neill’s time at St. Anne’s was also marked by a steady flow of letters to the Provincial, expressing his distaste for what was happening in our various seminaries, especially those in the Bay Area. These letters likewise reviewed what he felt was essential for priests and seminarians: a great desire for holiness, devotion to the interior life of our Lord, to His Holy Eucharist, and to the recitation of His Mother’s rosary, an ever-increasing loyalty to the faith and to the magisterium, a continuing interest in the missions (with a resulting enthusiastic encouragement of the U.S. Province’s venture in Zambia), and a better balance between studies and athletics. Though he himself enjoyed playing golf, he always felt that the seminary of his day gave too much time, attention, and reward to sports achievements over those of the classroom.

During his years at St. Anne’s, John had often expressed the intention of living his years of retirement at the Home with the Little Sisters. But then he had a prostate operation in 1986, and he began to see the wisdom of spending his final days in the midst of his Sulpician brethren. Accordingly, in the summer of 1988 he made application for a place at St. Charles Villa, and by October 8 of that year he arrived there, just ten days after Father Chudzinski had come from Seattle. A minor note: John got himself an exercise bike shortly after he moved in, but it has been gathering dust in one of the basement rooms for a long time now.

California did not fade into the background during his more than seven years of residence in Baltimore. For one thing, he had the joy of meeting Little Sisters who were assigned to St. Martin’s or who were visiting there who had previously labored at St. Anne’s in San Francisco. In addition, he made a few trips back to the West, mostly at the time of Sulpician gatherings, and these visits always included a stay in Redding to enjoy the closeness of his two nieces, Molly Steffen Rankin and Colette Steffen Spanfelner, and of his two nephews, Thomas and Michael Steffen. And Molly especially reciprocated with several visits to the Villa and with weekly phone calls to her Uncle John.

Life at the Villa settled into a regular pattern. Daily Mass was the center of his day, and he was quite conscious of the importance of preparing and giving good homilies, even to his confreres. His recitation of the rosary recalled his days at St. Anne’s when he daily led the public recitation of Mary’s rosary. And by his example and in discussion he was always ready to promote greater love of the Lord in the Eucharist. House meetings always evoked contributions from him, even if they tended to be reprises of his earlier strongly-held opinions. Childhood likes and dislikes about foods reappeared; he never wanted to eat any vegetables, and he was on a constant lookout for candies and cookies until doctor’s orders put him on a strict diet.

Then a gradual weakening set in, and there were no more trips to the West. Increasingly there were falls in his room and visits to the emergency room at St. Agnes’ Hospital. A week or so after Father Arand died, the authorities saw the need to move Father O’Neill to St. Martin’s, where for a time he was still able to concelebrate daily Mass. Molly Rankin paid a visit before Christmas, and her uncle assured her that he would celebrate the feast in heaven. He was off by about a month, but then early on January 26 he quietly slipped away to the life that never ends.

At his personal request (perhaps on the basis of some prayer experiences that he remembered from his St. Charles’ faculty days) his funeral Mass took place in the chapel of Our Lady of the Angels on January 30, after a wake service the evening before at St. Martin’s. The Provincial, Father Gerald L. Brown, S.S., presided and preached at the evening service and was the main celebrant next morning. Father William O’Keeffe, S.S., superior of the Villa, was the homilist, and John’s niece Molly served as lector.

Though he had wanted to spend his final days with his Sulpician brothers at St. Charles’ Villa, he still wanted to be buried with his family in Redding. Molly accompanied her uncle’s body to California, and the final Mass was celebrated on February 2 at Our Lady of Mercy Church in Redding, with burial in St. Joseph’s Cemetery there. Father Gerald D. Coleman, S.S., rector of St. Patrick’s Seminary, Menlo Park, presided and preached at the Mass for his former teacher and confrere. Others, besides the family, included two long-time friends, Father Arthur Wille, M.M., of the Maryknoll house in San Francisco and Father John Kavanaugh, pastor of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Church in Redwood City, California, who made a special trip for the Mass.

We have been blessed in knowing John O’Neill and also in enjoying his favorite niece, Molly Rankin. Even if we did not always agree with John in what he did and said, we will all come together in spirit on June 6, 1996, to mark the end of sixty years since Archbishop Mitty raised our brother to the priesthood. May the Lord already have welcomed him to a place at the eternal banquet in the heavenly kingdom, for which he had been striving and yearning for a long time now.

John W. Bowen, S.S.

Archivist