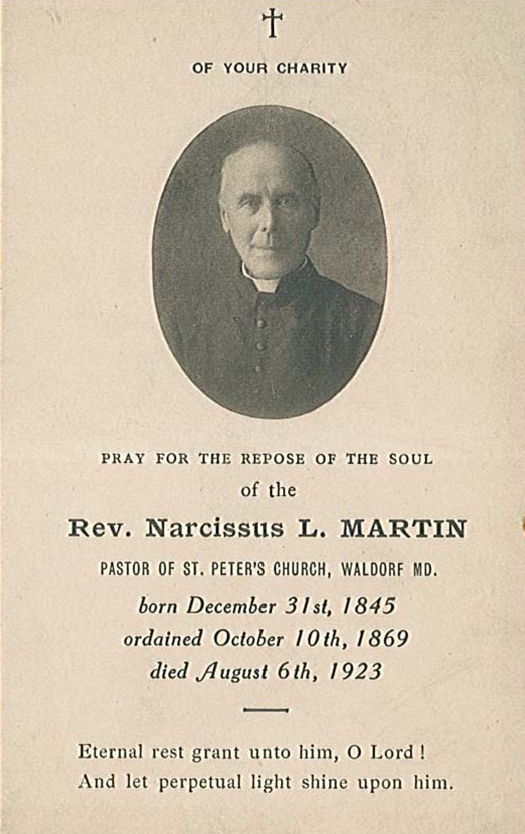

Martin, Father Narcissus

1923, August 6

Date of Birth: 1845, December 31

Paris

October 7, 1923

Fathers and Very Dear in Our Lord:

The obituary notice that I am addressing to you may surprise you. It concerns a confrere, Father Narcissus Martin of Baltimore, who successively spent some time in our seminaries in France, Canada, and the United States; and who, after these services of an intellectual type, dedicated himself for twenty-nine years to the evangelization of the Negroes of Southern Maryland without rest or respite – loving his people with zeal and passion, depriving himself, working, suffering, sharing in every possible way the misery which he looked on every day; ending by dying, poor and worn out, after fifty-four years of priesthood in the midst of his sheep, and blessing God, his relatives, his friends, even those who despised him.

How explain this life? Was he fickle? No! He was one of the men for whom traditions, restraints, security are too confining, who need space and freedom to really be themselves. They are encountered even among the saints: for example, the Blessed Grignon de Montfort, the Curé of Ars. Ordinary rules do not apply to them. They exhibit a strangeness of outlook, of work, of habits. They will go to the ends of the earth, to the outskirts of civilization, to be free. This last remark applies to our confrere, Father Martin. He certainly had all the qualifications of spirit, of heart, of dedication, to do the work of St. Sulpice. But while staying with us whole-heartedly to the end, in the jobs that were entrusted to him, he was only in passage. Young and even old, he gave the impression that his being with us was only a passing thing and that to fulfill his vocation he had to be alone. That detracts nothing from his worth before men nor before God. There is room in the Church for a small number of souls – beautiful, generous, heroic – who have a sense of free flight, who are right in saying that that is their nature and their gift; and at the same time have the humility to add: Don’t imitate me.

Let us examine Father Martin’s life in its various stages.

He was born in Aire in the Diocese of Arras on December 31, 1845. By reason of wealth his family held a high rank in that section of the country. By reason of its Christian spirit the family was even more esteemed. Two of our confrere’s sisters became Daughters of Charity. Yet living is a married sister, and at home a sister and a brother, both unmarried but exemplary Christians.

His father was a teacher. In watching out for what concerned him, in showing his affection, he saw to it that his children had not only social advantages, but also a Christian upbringing. A Christian himself, he passed on his faith and piety to all his family. The results are self-evident – God responded by inspiring the vocation which early developed.

A man of order, he established habits of order, of deportment, of strict regularity. When the son became a priest, he knew how to temper the enthusiasm of his nature to the more pedestrian considerations of keeping accounts, of propriety, of neatness. Even when he became the poor volunteer that we know, he always remained the man of good form and fine manners in all that pertained to his person, his dwelling, and especially God’s house.

Father Martin had his classical education at the college of St. Omer. He did honor to his teachers by his uninterrupted success.

Happy, too, was the father who saw a young talent blossom – happier still when his son said to him: “I want to be a priest.” There was already a predecessor in the family, his father’s brother, Father Jacques Martin, a member of the Society, teaching Theology in the seminary in Paris. That was a sign, an omen. After spending some years in his diocesan seminary, he came to Paris in 1867 to complete his theological studies. After that he went to Solitude in 1868-1869. In October of that last year, being only a deacon, he was sent to the seminary of Rodez. On October 10th he was ordained priest, and he eagerly took up his functions. He remained at Rodez for ten years during which he taught Philosophy, then Theology. Finally, he became Superior of the Philosophy students. As a Professor, he adhered to the strictest teachings of St. Thomas long before Leo XIII had insisted on their being reaffirmed through his encyclicals. As a Director, he showed himself a trainer of souls – a bit fiery – and a zealous recruiter of religious and missionary vocations. As Superior, he showed initiative. Characters like his do not act without attracting attention and provoking some clashes. St. Francis de Sales – who was familiar with the topography of mountain country – could have taught him that the straight path is not always the shortest and surest. That is to say, zeal for truth and duty achieves its purpose only with some twisting and turning.

In 1879 Father Martin was transferred to the seminary at Autun. He stayed there only a year. In 1870, at his own request, he was sent to the seminary in Montreal. After three years, he chose to go to the seminary of Baltimore. After another two years – again at his own request – he was named chaplain at St. Agnes Hospital. In 1894 an opportunity for giving satisfaction to his active nature presented itself – an opportunity such as he might have hoped for. The parish of Waldorf (Maryland) was open. Others had turned it down. For him that was reason enough for wanting it and for asking for it. It had a mixed population of farmers and Negro slaves freed by the Civil War.

The farmers were nearly all Protestants, well off and little disposed to welcome a pastor, much less to help him. The Negroes were mostly Catholics by baptism, but poor, uneducated, barely existing in their cabins, surly toward their former owners, jealous of those owners’ mansions, too poverty-stricken on their meager incomes to hope to improve their lot in the world.

The pastors who were there before him stayed only briefly. He remained and did admirable work as pastor. The confreres, religious missionaries, neighboring pastors bear witness. A visiting bishop, citing the results, said: “I verily wish that all in charge of parishes might be like him.” In short, his work was admirable in zeal, in religion, in charity.

Zeal he gave to all, but he lavished it on the Negroes to show them respect, to give them encouragement, to convince them of their own worth, to make them recognize their status as citizens and Christians, to open their minds to true religious living, to better their moral outlook and their material condition, to get them to establish Christian homes where each one had his proper place – father, mother, children, with the corresponding feeling of dignity, respect, order, decency conforming to their age and responsibilities. There were obstacles: the predominance of Protestants, mixed marriages, religious ignorance, promiscuity within the family, backsliding – always easy in this environment where the one was sure not to be publicly frowned on and the other not to be punished in law. Not having the power to wipe out these obstacles, he attempted to dilute them and neutralize them. There were there some good souls and, in several instances, an unexpected blooming of true virtue.

Religion he exercised in his church which he made worthy of God and attractive to the faithful who previously had been tolerant of neglect – let us rather say – of disorder and dirt. He was his own sacristan, his own bell-ringer, his own caretaker – the man who, always on the alert, did all the jobs, even the most humble, and fulfilled to the letter what St. Jerome said of his disciple, Nepotian: Erat sollicitus Nepotianus si nitreret altare, si rarietes absoue fauligine, etc. … [Nepotian wanted the altar to be neat, to be without a speck of soot …]

Religion he exercised again in the care he took in being punctual for Mass in his parish church and in a mission church about two leagues [about five miles] away. He maintained that punctuality in all kinds of weather, despite bad roads, always fasting – and that for the whole time of his ministry without ever having a vacation, or time off, or any help.

Imagine the heroism of this priest as, on Sundays, he left at five in the morning to go to say a first Mass at a distance, as he returned at midday for a second Mass. Within these hours he had to fit in talks, catechism lessons, the settling of some matters, the care of the ill and the poor, the overseeing of other things. That was just Sunday’s work. But the week had its share of parochial visitations, instructions, keeping in contact with a population so diverse where the man of means very frequently disdained and rebuffed the poor man as beneath contempt, set in his ways, repugnant.

Charity he exercised by using his own modest resources to get some things going in his parish and to contribute generously to works in the diocese and beyond. It was especially to his credit that he refrained from making any direct appeal to his parishioners in his talks in church. He did not even take up a collection. One will ask himself how this pastor was able to carry on worship, build a very decent rectory, lay out a fine parish hall, provide a shelter for orphans, arrange from time to time for missions at the parish, always have something put aside to help the needy. How? Providence has its secrets for inspiration and for miracles. One day a rich benefactor, touched by the good he saw being done, gave Father Martin a large farm. The recipient viewed this as a spur to his initiative. He became a gentleman-farmer. He put in various crops, did some breeding, acquired several horses which he used as carriage horses, plow horses, riding horses for apostolic work. The parish, already alive spiritually, became alive materially. It has the possibility of going on and lasting; and dead though he be, opera sequentur illum [his works live on after him].

Twenty-nine years of service in the conditions we have just described – that is a recommendation and the promise of a beautiful bouquet to bring to Heaven.

One day in November 1910, as I was on a visitation to the seminary in Baltimore, Father Martin came to see me and said: “I am still healthy enough for my ministry, but I am getting older and I may become unequal to it. If that happens, will you let me come to Issy?” “Yes,” I replied to him, “we shall never turn our backs on a confrere. But considering the way you are, it does not seem to me that that is the way things will turn out.” (He was one of those who, put in a cage, would pine away and die.) “For we want you to go on living.”

As a matter of fact, he lived and worked up to 1923. In 1919, they celebrated his fiftieth anniversary as a priest, and it was a great joy to him to see gathered around him a good number of confreres, priests, and seminarians. For him the celebration went on until November 21st, when he celebrated Solemn High Mass in the presence of Cardinal Gibbons and hundreds of priests who had come to St. Mary’s from all parts of America.

A first decline in health occurred on February 4, 1923. From that day on his confreres took turns in going to take his place and to help him, at least on Sundays. On August 4th he said his last Mass. On Sunday, August 5th, he was happy to have Father Milholland with him. On Monday evening, August 6th, he received the last sacraments. There followed a brief period of death agony, then death. On Thursday, August 9th, Father Dyer held a funeral at Waldorf. The body was then transferred to St. Mary’s in Baltimore; and after this last display of charity, after another Mass in the seminary chapel, the body was buried in the little cemetery on the grounds.

I recommend Father Martin to your prayers, and I renew to you my very devoted sentiments in Our Lord.

H. Garriguet

Superior of St. Sulpice