Dillon, Father Charles Patrick, S.S.

2003, July 29

Date of Birth: 1914, August 21

September 15, 2003

Join the Sulpicians and see the world. Or, at least, enjoy a variety of priestly ministries and academic careers in widely separated geographical locations. That is a fair description of the active years of my friend and classmate, Father Charles Patrick Dillon.

Sulpician Assignments

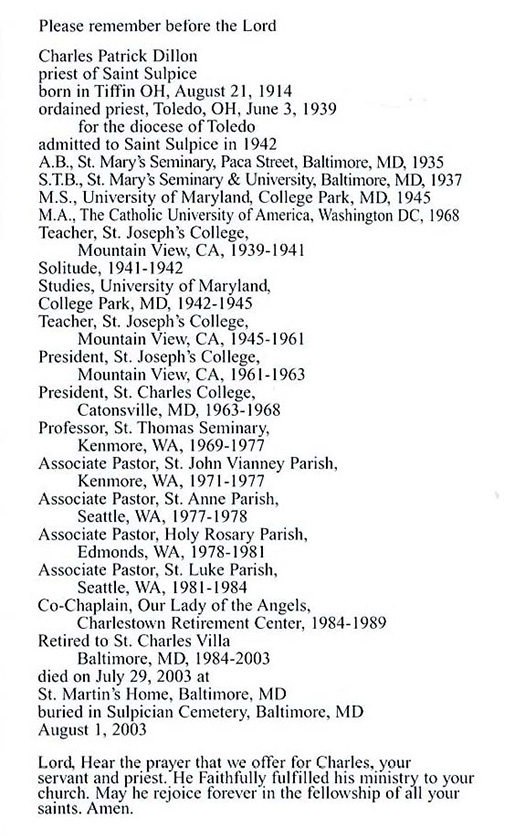

During the forty-five years when he was fully active, he taught in four different seminaries, was president of two of them successively, and served as associate pastor in four different parishes. He was originally trained in and successfully taught chemistry. He also did an impressive job of instructing seminarians in English literature and composition, with special emphasis on speechwriting. Later, after another period of retraining, he became a professor of psychology.

Father Dillon’s duties took him to St. Joseph’s College, Mountain View, California for sixteen years; to St. Charles College, Baltimore, Maryland for another five; to St. Thomas Seminary and then to several parishes, all in Seattle, Washington for an additional fifteen. Even after he retired to St. Charles Villa in Catonsville, MD, at the age of seventy, Father Dillon worked for another five years as Catholic co-chaplain at Charlestown Retirement Center, on the site of the former St. Charles College. When serious illness overtook him, he transferred to adjacent St. Martin’s Home, where he died on July 29, 2003 of the second of the two serious illnesses that overtook him in his long life.

An earlier serious illness, in the form of massive internal bleeding, had almost caused his death while he was President of St. Charles College in the mid-1960s. The faculty and seminarians in Sulpician-staffed institutions throughout the United States carried on a campaign of prayers for his recovery for many weeks while the doctors performed varied surgical procedures. Father rallied and eventually recovered completely and went back to work.

Teacher, Disciplinarian and Spiritual Guide

Most former seminarians, thinking back on Father Dillon’s qualities as teacher and administrator, almost certainly would first recall his strictness, and I believe this would neither surprise nor displease him. He meant business, demanded much, and stayed his course unswervingly. Student lore is filled with stories about his classroom manner and about his administrative techniques.

Some of these tales are exquisitely funny. For example, the case of the nervous reader. It went something like this: Because Father Dillon’s personality so dominated the scene, imaginative seminarians had given him such nicknames as “Zeus” and “Almighty God.” When, at St. Joseph’s, a new form of communal night prayers, with a different version for each evening of the week, had been introduced into the schedule, the student-reader, on one occasion, began the wrong version for a given day and, of course, received a reply of dead silence from the 500 seminarians when it was their tum to respond, since they were reading from the correct page and he was not. He was ordered by the student in charge to begin again — but on the page for that day. Twice, he began again to read from a wrong page. At this point, Father Dillon, as president, rose from his place to take charge, just as the student finally began the correct version. The student body went wild with laughter when these words came forth: “Forgive me, Almighty God, for all I have done to offend you.” The president did not look amused.

Another former student tells about an incident, not humorous but quite characteristic, in the chemistry laboratory over which Father Dillon was presiding. On the day in question this student, having completed his assigned tasks, was merrily conducting a private “experiment,” simply mixing chemicals at random. He describes the result: “There was a ‘swoosh’ and then a really neatly colored cloud of smoke.”

Fr. Dillon was at the young man’s side immediately, demanding to know which chemicals the student had used, apparently fearing that something toxic might have been produced. The young man admitted that he had absolutely no clear notion of what the ingredients had been. Rather quickly, the cloud dispersed, with no discernible harm done.

Later Father called the student to his room to scold him about the potential danger he had unleashed but mostly to criticize the young man’s lack of scientific method — his failure to record in advance what chemicals he was using in the experiment. Who knows? — he may have made an important discovery!

Besides inspiring fear in his students of chemistry, Fr. Dillon also elicited their respect and gratitude, mainly for the masterful way in which he gave them a good overview of the history of the science by escorting them from one important discovery to another.

Acting in a completely different capacity than that of teacher or disciplinarian, he was met with not only respect but admiration and a good measure of affection. I refer to his work as spiritual director of individual seminarians.

Sulpicians holding the post of president or prefect of discipline (later re-named “dean of students”) were not permitted to act as confessors or spiritual directors of their students because of the potential conflict between the confidentiality requirements of this duty and the public nature of either of the other two roles. Whenever he was not holding either of these managerial positions, Charlie relished the opportunity of performing the more pastoral work of spiritual guidance and apparently was a successful counselor, as several former seminarians have testified. One of them, years later, recalls his “10-10-10” plan for those for whom he was spiritual counselor: a daily ten-minute visit before the Blessed Sacrament, another ten minutes devoted to spiritual reading, and a third to Bible reading.

Pastoral Assignments

His final apostolate was an entirely pastoral one, the ministry he exercised as associate pastor in three different parishes in the Seattle area and, after retirement, in service to the Catholics living in the Charlestown Retirement Community near St. Charles Villa. People close to him in those days sensed that this was by far the happiest period of his life. In this environment he felt free to be much more relaxed and approachable. He was as conscientious as ever but now in a very personable way. The parishioners described him as kind, friendly, warm, eloquent in the pulpit, good-natured, and gregarious.

A fellow priest of the Seattle Archdiocese is quoted as saying: Charles Dillon found an agreeable niche in pastoral ministry and loved serving people. He taught me a deep respect for the Sacrament of the Sick. Later on, his fellow residents at St. Charles Villa noticed this same love for “Anointing.” In fact several times during his early sickness he arranged to be anointed publicly in the midst of the Villa community.

Those acquainted many years ago with Fr. Dillon, the demanding teacher and strict disciplinarian, would have been delighted had they had the chance to know him during his later years as associate pastor and to see how beautifully he had mellowed. They would be further pleased to know that he then regretted the harshness of his earlier attitudes and methods

Declining Days

During his final illness in the infirmary of St. Martin’s Home, Father Dillon was almost invariably cheerful, although he suffered a considerable amount of pain. This illness lasted for several years during much of which he was bed-ridden and, of necessity, often alone. Towards the end he was scarcely able to move or to speak much above a whisper, but his ready smile rarely left him. His aforementioned students from the old days would indeed have been probably surprised and undoubtedly amused and heartened had they been able to hear the nurses and other aides who tended him refer to him affectionately as “our Father Chuck!”

Charles Patrick Dillon, the son of Warren Patrick Dillon and Caroline Marks (who would be considerably over a hundred years of age at the time of her death) was born August 21, 1914 in Tiffin, Ohio. After graduating from St. Charles College in 1933 he entered St. Mary’s Seminary for his four years of theology. During part of that period he was active as a street preacher in Baltimore as part of the Catholic Evidence Guild. Charlie was ordained for the Diocese of Toledo and the Society of St. Sulpice on June 3, 1939. After two years of teaching in California he entered the intensive Sulpician formation program known as Solitude and formally entered the Society in the spring of 1942. He soon returned to student status, first at the University of Maryland and then to Catholic University, where he earned degrees in science and philosophy. Then followed his thirty-nine years of teaching and administration and his nineteen years as resident at St. Charles Villa and St. Martin’s home, where he died on July 29, 2003. The funeral Mass was celebrated on August 1, 2002, in the Chapel of Our Lady of the Angels, Charlestown Retirement Community, Baltimore, followed by interment at the nearby Sulpician Cemetery. The Sulpician Provincial Superior, Father Ronald D. Witherup, S.S. presided at the Mass, surrounded by many friends and especially by many Sulpician confreres. Father John Mattingly, S.S. was the homilist.

Father Dillon was preceded in death, in 2002, by his sister, Mary Hage. He is survived by his brother John, of Toledo, Ohio, by eight nieces and nephews and by numerous grand-nieces and grand-nephews.

After a life of conscientious and self-giving service to so many seminary and parish communities and many years of patient suffering, may his soul rest in the embrace of his loving Father. Amen.