Gleason, Father George

1955, November 9

Date of Birth: 1887, February 14

Paris

February 8, 1956

Fathers and Dear Confreres:

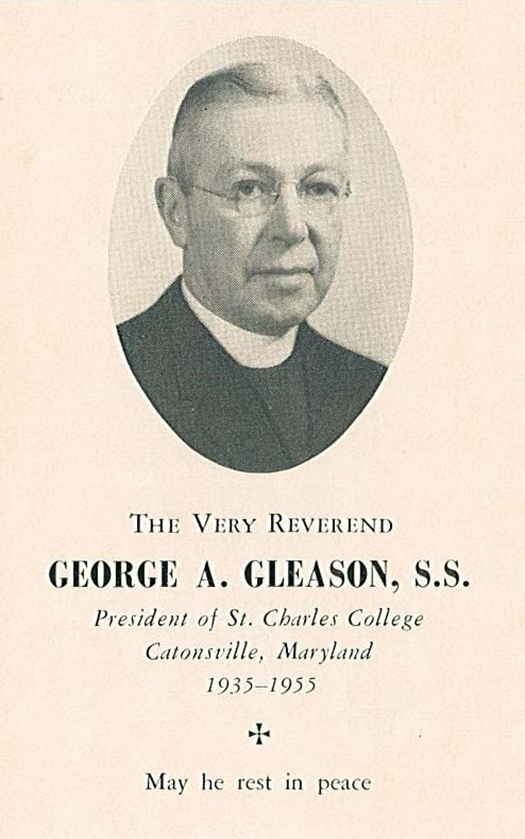

Our American province, already so severely put to the test during the last scholastic year, was saddened at the opening of this one by the loss of one of its most eminent members, Very Reverend George Gleason, President of St. Charles College and first Provincial Consultor. One of his former students summed up his personality in these words: “A perfect gentleman and a true priest.”

In November 1953, when he did me the honor of “his” college with his customary courtesy and delicacy, I found him full of life and vigor; and I did not foresee an end so near. Led by him to the little cemetery – so simple and so touching – where our confreres are buried, I was far from thinking that the first member of the personnel of the house to be buried alongside his predecessors would be the one who was then reciting with me the De Profundis.

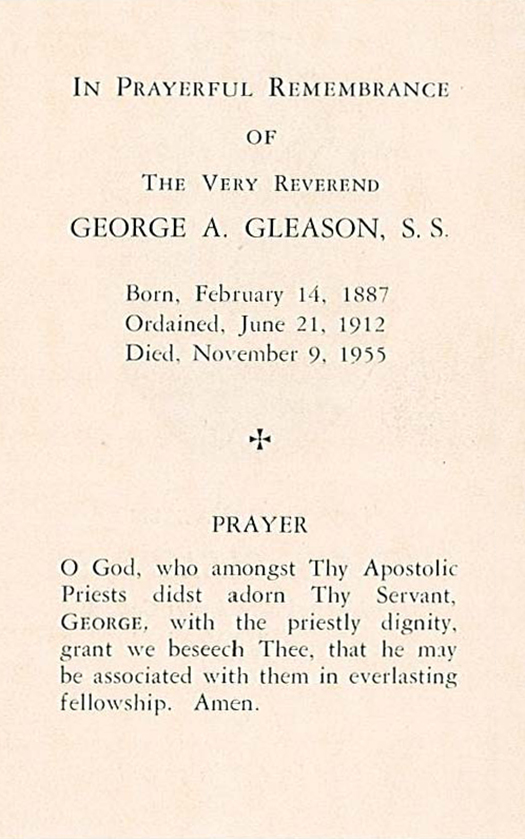

George Gleason was born in Providence, Rhode Island, on February 14, 1887. The thought of being a priest took root very early in the soul of the boy. Having finished high school, he entered the minor seminary of St. Charles at Ellicott City in the far outskirts of Baltimore. After two years he went to the major seminary, St. Mary’s. At the end of his course, he was ordained priest on June 12, 1912 by the renowned Cardinal Gibbons.

He spent the following year at the Catholic University in Washington, where his plan to dedicate his life to clergy training in the Society of St. Sulpice matured. In 1913 he began his Solitude (then in Washington) and met Eugene Harrigan who was to become his most intimate friend. Both were candidates of exceptional worth, and their coming was regarded as a blessing for our work. After scarcely two months, a breakdown of health forced Father Gleason to take a long period of rest. For that purpose, he was sent to St. Charles.

His Excellency, Bishop Shehan of Bridgeport, in the eloquent panegyric he preached on the day of the funeral, delicately recalled that in those distant days, himself a student, he had been assigned to appear before the convalescing priest. He described his meeting with him like this:

“I saw a man of medium height whose slender and straight figure gave the illusion of being taller than it was. He seemed very young, with a smiling face, and a charm which soon put one at ease and encouraged friendly conversation.”

The first impression given by the college must not have been very favorable. The buildings at Ellicott City had burned down eighteen months before, and the seminary was just being reestablished at Catonsville in the immediate environs of the city. With old structures threatening to collapse, still more depressing under the gray skies of a bleak November day, some simple new starts which scarcely allowed the envisioning of today’s splendid buildings – that is what was presented to the new arrival.

He expected to be there for a brief period of recuperation. He was to stay there for forty-two years and to dedicate all the effort of his priestly life to it.

His charming personality and his engaging character soon made him accepted by the faculty. He did not long remain idle, for it was still remembered that, as a student at St. Charles College and St. Mary’s Seminary, he had been an organist with talent rare in a young man. It was remembered, too, that in the choir he had been a soloist. His voice was equipped to give to the liturgical texts overtones of the faith and love which filled his soul. It called forth an intense religious response from those who were listening to him – for example, in the Dies Irae, or in the offertory of such a Mass as the Requiem Mass.

He was put in charge of Chant. By his competence and the enthusiasm, he engendered, he succeeded in forming one of the most beautiful choirs that a minor seminary had ever had – and one which a major seminary might have envied. Here let me become personal: at the last Chapter in Issy in 1952, when Father Gleason went into the chapel, his old musician’s instinct slipped out and he climbed up to the loft to try out the organ. From memory he played several classical pieces and did a variety of improvisations.

Deeply interested as he was in that art, he knew, however, that he had not become a Sulpician merely to train other musicians. By taste as well as by duty, he involved himself in everything that concerned priestly formation.

The occasion for such involvement was not long in coming. During the school year, Father Coyle, teacher of English literature and composition, was stricken by sickness. His classes were turned over to Father Gleason. His inborn delicacy had always given him a respect for fine language and precision in the use of words. His knowledge of English, his style in speaking, the clarity of his exposition, all soon allowed him to be effective. It was no longer a question as to whether the new teacher would leave the college where, from the beginning, he had found his life’s road.

It might be thought that a mind so highly cultured would be more at ease with the older students who could profit the most from a classical education. On the contrary, it did not take long for him to demonstrate his skill, even his preference, for another kind of student. In America, like everyplace else, to get into the heads of young boys the mysteries of Latin declensions and conjugations or the basic rules of syntax is a hard job for teachers and students. The study of the language of the Church is an essential part of priesthood preparation. His liking for youngsters made him happy to take the first high class for nearly twenty years. Still later, as Superior, he continued to concern himself with the little group of slow learners to whom he made it a point to give particular attention.

Thus, his life was spent in the conscientious carrying out of his various duties with nothing hinting at the next development.

On August 31, 1934, he was, as he had been for many years, in a little parish in the Diocese of Portland in Maine, when he received a letter from the Provincial Superior, Father Fenlon. His friend of long standing, Father Harrigan – who had been his colleague and then his Superior at St. Charles – had been stricken with paralysis and Father Gleason was appointed to succeed him. A little later the appointee opened his breviary to anticipate the next day’s office. In it he read this passage from Ecclesiasticus: “Rectorem te posuerunt? Noli extolli; esto in illis ouasi unus ex ipsis – curam illorum habe … decet enim te primum verbum diligenti scientia et non impedias musicam.” [Have they made thee “Rector”? Be not lifted up, be among them as one of them … It becometh thee [to speak] the first word with careful knowledge and hinder not the music.] He was deeply impressed by the appropriateness of this first nocturne and he made it the rule of his presidency. He did, however, just about give up being involved in music because the running of the oldest and most important minor seminary in the United States did not leave him time for music.

His presidency was a burdensome one, for the [financial] situation of the college was, if not critical, at least very serious. The country was still undergoing the effects of the severe economic depression of 1929. Enrollment had plummeted, debts were dangerously large. The success the new president had in facing and overcoming these material pressures is demonstrated by what the college is today. For certain, the return of prosperity and some magnificent donations also played a part, but the recovery comes back in large part to Father Gleason’s work in interesting the alumni, clerical and lay, in the needs of this very necessary institution, which was struggling to stay in existence.

Under his superiorship, St. Charles College prospered more than ever, the number of its students greatly increased, buildings were finished, financial worries were left behind.

Those matters, however, were not the Superior’s main concern. He strove with even more care to maintain and even to better St. Charles’s worth as an educational institution. Wanting future priests to have a training at least equal to that of young men of the world, and also wanting students who did not go on to priesthood to be able, with no penalties, to be accepted at institutions of higher learning, he sought for and obtained recognition of the minor seminary from the Middle States Association of Schools and Colleges. In consequence, he organized class material, and the level to which he raised his house was evidenced by the trust that the officers of the Middle States Association showed him in calling on him, as often as possible, to be a member of a committee charged to evaluate other colleges. It was also evidenced by his election as president of the grouping of minor seminaries of the United States at the Catholic University in Washington.

Meanwhile, his concern was not limited to the students. He wished to strengthen the bonds of affection between the alumni and their Alma Mater. By his great kindness, by his absolute devotion, by the welcome everyone was sure to receive, he had done much to rebind to St. Charles the lay alumni as well as the priests. Their pleasure at feeling again at home in the house of their youth was apparent whenever they had a reunion.

A seminary is equally a company of teachers. Anyone who knows the difficulty of molding a unified body out of a group of individuals, Father Gleason’s most remarkable work during the twenty-one years of his superiorship was the zeal for the work and the team spirit which he breathed into his co-workers. At the head of one of the largest Sulpician communities whose members were involved in a job always obscure, often monotonous, sometimes frustrating, he created feelings of loyalty to the college and enthusiasm for its welfare. He did this by a genuine kindness, by a great spirit of charity, by an understanding of characters quite different from each other, by a deep piety towards Our Lord, and by a love for the priesthood.

During his illness, the many signs of affection which his confreres showed him, the fear they expressed of being without his leadership, the wishes they spoke of seeing him at least return to Catonsville even with his activity cut down, were merely sensible signs of their inner feelings.

For forty-two years Father Gleason was thus identified with his seminary. The day when a separation would be necessary seemed still so far away that no one ventured to think of it. God had decreed otherwise.

On the evening of last August 18th, he suffered a heart attack which paralyzed his right side and put his life in danger. Little by little he recovered some strength; so much so that hope sprang up that he might be able, after Christmas, to return to St. Charles, his dear St. Charles, to go on giving the college the benefit of his wisdom and experience. But on the afternoon of November 8, a new attack occurred and was followed by another the next day. The patient then lost consciousness and died that evening surrounded by his confreres and his two sisters to whom he had always remained very much attached.

The funeral took place on November 14th in the college chapel. Present were nine bishops and numerous priests, some of whom came from quite a distance. The numbers at the funeral constituted a magnificent tribute of the esteem so well deserved that his students held for their teacher of an earlier day.

The whole Society’s grief is great, but no less great is our consolation for this good servant has been welcomed in Heaven, not only by his well-beloved Master, but also by his dear friend, Eugene Harrigan, and all the other confreres who received him at St. Charles in 1913 or had ever since worked with him.

Again, I recommend to your prayers the soul of our dear deceased, and I renew to you my sentiments of affectionate devotion in Our Lord and Our Lady.

Pierre Girard

Superior General of the Society of St. Sulpice