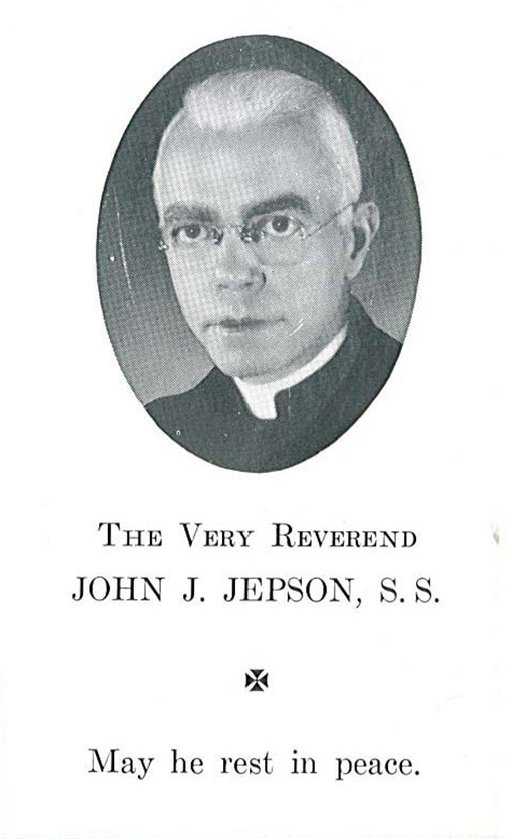

Jepson, Father John

1951, January 10

Date of Birth: 1882, February 12

Paris

January 25, 1951

Fathers and Dear Confreres:

Over a number of years our Washington confrere, Father Jepson, suffered from diabetes. That disease did not, for a time, keep him from continuing to exercise his functions. But the time came when he had to give up. It was then that came the ills which too often plague the aged. His eyesight failed. Intellectual work became impossible for him. He had to enter Georgetown Hospital. It was there that he was called to God on Wednesday, January 10th, in the aftermath of a cerebral hemorrhage. For your benefit I would like to recall him and go over his life.

John James Jepson was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, on February 12, 1882. His parents, James Jepson and Elizabeth Nuttall, were staunch Catholics. Their faith was for them – as for all of us – a gift. But, as their own experience and that of their children bore out, it required of them a choice of being true to it or of compromising it. With all their hearts they made the right choice.

Our future confrere began his elementary studies at St. Joseph’s parish-school. He continued at the Cathedral School in Wheeling. Since John Jepson wanted to be a priest, he left Wheeling in 1897 when his parents sought for and obtained his admission to St. Charles College. This institution, owing to the generosity of Charles Carroll of Carrollton, Washington’s companion and signer of the Declaration of Independence, was entrusted to the Society of St. Sulpice. It was still on its original site (only later did fire destroy it) at Ellicott City. It was there that John Jepson was going to spend four years, from 1897 to 1901.

There he met a close friend some few months his junior, whom he found himself seated next to by reason of alphabetical arrangement. That was Peter Leo Ireton, who was to remain forever his faithful friend and who, today as Bishop of Richmond, preached Father Jepson’s eulogy on the day of his funeral. Both at St. Charles College and St. Mary’s Seminary, they were always close to one another. Thanks to Bishop Ireton, we are informed as to our future confrere’s years of preparation for priesthood. “He gave,” he tells us, “the impression of being the student most serious and most conscientious about the demands of his vocation. Others, to start with, had more talent; but the years, with the vast amount of work, the application to study, the eagerness to learn, allowed him to go up step by step to the ranks of the best – such was the common opinion among his fellow students.” We learn from other evidence, “His piety went hand in hand with his work.” It was during his years in the major seminary, St. Mary’s, that John Jepson rooted and strengthened his union with Our Lord, his love of the Eucharist, and his filial devotion to the Blessed Virgin. He came to his independence of spirit in the midst of opinions already expressed; to grandeur of spirit without pride; to humility without servility; to self-sacrifice without warping of personality. Everything contributed to that complex purpose for him, but above all, intellectual work.

Before he entered the seminary, he had learned shorthand. Of that skill he made use (with an application and a zeal almost too intense) to preserve – mysteriously for mere mortals – the essentials of lectures, and to make notations in his precious books, his pride and joy! As subdiaconate neared, he took care to note in shorthand at the beginning of each psalm the main idea and the lesson that the psalm contained. Out of this practice there grew in him an extraordinary knowledge of Holy Scripture, the accomplishment usually of Scripture specialists. Out of his immersion in this study came his extraordinary knowledge along with his intimate and personal consciousness, the fruit of his daily and private meditation. Later on, he came to a realization of his knowledge and made use of it in the priests’ retreats he gave and in the sermons he was asked to deliver on various occasions.

His studies, you can imagine, were crowned with success. He was a Bachelor of Arts in 1902, a Master of Arts in 1905, and a Doctor of Philosophy in 1915.

On June 21, 1906, Father John Jepson was ordained priest at Wheeling in his own diocese by his Ordinary, Bishop Patrick Donahue. In what direction was he going to aim his priestly life? When he was in the seminary, his fellow seminarians teased him, a bit archly, about wanting to be a Sulpician. He smiled or brushed aside their remarks. But, in fact, he had no such idea. His whole desire was to serve the Church in his native diocese, wherever his bishop might send him. The bishop was thinking of making special use of him in spiritual service to emigrants from Central Europe. To this end, the bishop pondered sending Father Jepson to the Universities of Krakow and Prague to study Polish and Czeck. But, at the same time, our confrere, Father Dyer, Superior of St. Mary’s Seminary in Baltimore (the first Provincial Superior of St. Sulpice in the United States) asked Father Jepson’s bishop for Father Jepson’s services for a year or so in a teaching assignment at St. Charles College. Bishop Donahue alerted the young priest to what was in the wind, and he generously left the decision up to him of going to Europe or functioning in the capacity that Father Dyer wanted him to function in. Father Jepson knew his bishop’s affection for and gratitude towards St. Sulpice. Suspecting what the bishop would prefer, he sacrificed the first project and opted for the assignment that Father Dyer wanted him to take. Without being a Sulpician, he went to labor with the Sulpicians and to live their life.

At St. Charles College, Father Jepson taught Latin and English. He filled that dual role for five years, up to 1911. No doubt he was won over to the Sulpician life, for in that year he asked to be admitted to the Society. His request was approved – at least in principle – for in 1911 he entered the Solitude, then in Washington. He was admitted in 1912 and the following year, while exercising all the functions of bursar at Caldwell Hall, the Divinity College, he began work on his doctorate in Philosophy, which he would obtain in 1915.

He was then again appointed to St. Charles College in Catonsville, the site which had replaced the fire-destroyed site at Ellicott City. He was teaching the same subjects as he had previously taught with the addition of Greek. But he was to be at Catonsville for a first stay of only three years. In 1918, Father Dyer, the Provincial, sent him to the other side of the United States, to Mountain View in California. A dual Sulpician seminary was founded there at the end of the nineteenth century by the Society on the insistence of the then ordinary, Archbishop Riordan. On the same grounds, on a magnificent site in a charming climate, were a minor seminary and, in with it, a major seminary of Philosophy and Theology. Father Jepson was appointed to the minor seminary, distinct from but not separate from the other. There he was named to teach Latin and English. He remained there, filling with conscientiousness and with great success, the functions entrusted to him until the time when Archbishop Hanna of San Francisco built at Mountain View St. Joseph’s College, to which the students of the minor seminary moved in 1924. That new house required a superior. Father Jepson was chosen. Organizer of the new minor seminary, he remained its superior until 1932.

In 1932 our confrere returned to St. Charles College where he taught his usual subjects, but only for a year.

You see, there had been established at Washington, at the university, Basselin College, a School of Philosophy attached to Theological College, that is, to the seminary of Theology. In 1933, Father Jepson was named its first superior. Starting in 1935 he also became Vice-Superior of Theological College.

In all these offices Father Jepson showed himself to be, and was, the good worker for Our Lord and the Church. He was well aware of his duty of state: always ready to move when the bell called him, hearing in it only the voice of God; very faithful to the lengthy prayers called for in our Constitutions; as recollected in prayer as can be; open to all areas of human knowledge and to all community activities; endowed with a remarkable memory; as interested and absorbed in a problem of mathematics as in a text difficult to translate or interpret. He made his presence felt by his knowledge and his many intellectual skills. When he was with students young or old and had occasion to speak to them publicly or privately, he answered their questions or addressed them with such conviction that his voice would vibrate and affect his whole being with a force whose sincerity no one could doubt. He lacked neither ideas nor facts or quotations to embellish his talks. His knowledge, rich in thought and fact, and his diction (perhaps too staccato) strengthened each other like the fruit of deep reflection and a life of intense prayer.

But you would be very much mistaken in regarding Father Jepson merely as a learned man or thinker, or even a mystic carried away by pure contemplation. This Sulpician, in looks a bit austere, in speech, plain and pleasant, was especially a man of charity, simple, humble, and helpful. In 1938 the writer of these lines was in the United States. He was ready to begin the visitation of all the Sulpician houses in that vast country. He needed a travelling companion. Father Jepson offered to be that companion. He wished to be of service, to see again the seminaries of the West where he had worked so long and so well; and he had in mind to visit his sister, Miss Angela Jepson of Palo Alto. Father Jepson’s offer was gratefully accepted. The visitor of that already distant time remembers with emotion and gratitude all the delicate attentions with which his companion enveloped him so as to have him spared as much as possible the fatigue of that long trip, and to have him benefit from the pleasure that such a journey can give.

Unfortunately, even at that time, Father Jepson was experiencing in a mild but evident way the first signs of the illness, diabetes, which was little by little to become worse. Once while we were en route, and another time while we were at St. Patrick’s Seminary in Menlo Park, our confrere had to take some rest; and his companion, all the way across the United States, had to take on, for good or ill, the duties of infirmarian. That was only a brief warning. Father Jepson still had ahead of him a long time to work in the Sulpician Seminary in Washington in training the clergy. But the older he grew, the worse his illness became and the more it became necessary for him to struggle in the face of his duties as superior. You can imagine how rugged that struggle was when you think of his fidelity to the demands of prayer mornings with the community; of Spiritual Reading, which he prepared with meticulous care and into which he poured his soul, forgetting his suffering or hiding from his confreres and students the actual state of his health.

But the day came when he had to admit defeat. Fatigue increased, strength diminished, sight failed. Farewell to Sulpician work, which was so dear to him, and to the most essential parts of which he clung: suffering and prayer. Farewell to his work of translation for the new edition of the Fathers, such as St. Augustine’s Commentary on the Sermon on the Mount or St. Ambrose’s De Officiis! There were other publications to be readied, such as a volume of Particular Examens and an English translation of the Psalms, which would perhaps never see the light of day!

No doubt Father Jepson suffered from all these sacrifices. But with his habitual generosity, he offered them to God in order to enrich, by this offering, the long work of priestly training to which he had dedicated his whole life.

That life went on, first amid his confreres, then away from them at Georgetown Hospital. It went on humbly, silently, divided among prayer, the acceptance of pain, and the visits of confreres and friends.

At the beginning of January, Father Jepson’s condition worsened. On the 10th, almost without warning, the episode I mentioned hastened his call to God. His spiritual life was so intense, so sustained, so dazzling to his students and friends, that – according to the words of one of his followers who knew him well – “In entering Eternity, he did not feel like a stranger there.”

Father Jepson’s funeral was held in the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception at The Catholic University of America in Washington on January 13th. The Pontifical Requiem Mass was sung by His Grace, Archbishop Patrick A. O’Boyle, Ordinary of the diocese. Two bishops, their Excellencies John M. McNamara, Auxiliary of Washington and Patrick J. McCormick, Rector of the University, were present at the services. A third, whom we have already mentioned, Peter L. Ireton, Bishop of Richmond, recalled in his sermon, full of love and understanding, the principal stages of the life of his classmate and friend, John James Jepson.

After noting that one could illustrate with facts culled from the life of Father Jepson most of Our Holy Father’s exhortation Menti Nostrae, the Bishop of Richmond ended his talk with these words addressed not only to his hearers in Washington, but to us all: “Starting from the day of my consecration, with the respect so natural in all Sulpicians as regards the Episcopate and the members of the hierarchy, Father Jepson never let escape his vocabulary my first name, so at home on his lips from our days in college and the priesthood. Now I have the impression he is telling me: ‘Bishop, forget everything else you have said. Only ask your audience – my confreres, the priests whose companion I was, the seminarians whom I tried to train – ask them to pray and to continue to pray for me so that the One Who began in me the work of salvation may go on with it to the finish until the day of the Lord Jesus in such wise that I may finally have a share in the Chalice of the Lord in the kingdom of the Father.’”

Please accept, Fathers and dear Confreres, the expression of my very heartily devoted affection in Our Lord.

P. Boisard

Superior General of the Society of St. Sulpice