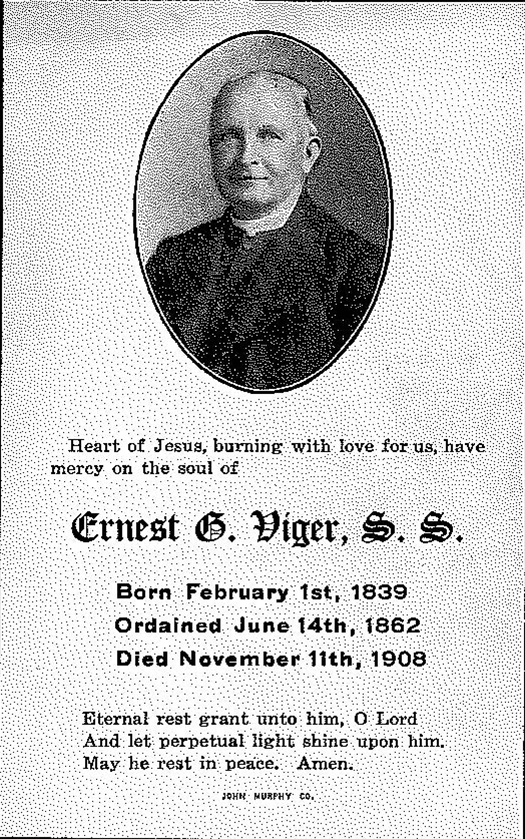

Viger, Father Ernest George

1908, November 11

Date of Birth: 1839, February 1

Paris

December 20, 1908

Fathers and Very Dear in Our Lord:

In the death of Father Viger, the fine work of the minor seminary of St. Charles has just lost one of its oldest, most devoted, most tireless workers. Last November 10th, feeling himself already suffering, he nonetheless wished to teach class, and in the evening he was blaming himself for being able to correct only half of his (students’) papers. During the following night God called him to Himself, dispensing him from the rest of that task, from which he had perhaps never in forty-six years of teaching dispensed himself.

Father Ernest Georges Viger was born on February 1, 1839, at St. Jacques de L’Achigan, a parish noted among all those in the Diocese of Montreal for the abundance of its priestly vocations. Both parents of our future confrere have left a name famous in the patriotic and political history of French Canada. His father had earned the fine nickname of “Doctor of the Poor.” Ernest George and his brother, today pastor of Epiphany parish in the Diocese of Joliet, exhibited very happy dispositions for piety and study. In order to encourage them, the family settled in the town of Assumption, already renamed for its college. After he had finished his classical course our future confrere entered the Grand Seminary of Montreal, at that time situated in the lower city under the same roof as the college and not far from Notre Dame Church. He was thus familiar with nearly all Sulpician life in Montreal and desired it for himself. That is why, from 1859 on, he was sent to Paris where he spent two years at the major seminary. Having received diaconate at the time of Trinity in 1861, he made in the following vacation a trip to Rome, where he was drawn especially by the desire of seeing the Holy Father.

The audience which he was fortunate enough to get with Pius IX made a deep impression on him and remained one of the great memories of his life; so much so that he kept as a relic the cassock which he wore that day and hoped to be buried in it. In the next October he entered Solitude. It comprised that year the list, rarely equaled, of twenty-one names; four of the Solitaires came from Canada, one – also destined for Montreal – was an Irishman. The Superior, Father Caval, ill the whole year at St. Giron, was filled in for by Fathers Renaudet and Ardaine. The presence of Fathers Brugère and Fouard among the Solitaires helped to make that year’s community a very lively one.

Father Viger had there a very good reputation, giving during the time edification, and charming his confreres by his piety, his regularity, his attempts to be helpful in every way, and his likeable character.

Toward the end of his year of novitiate, the Montreal Superior, Father Granat, was in Paris. He had been told that St. Charles very much wanted a Canadian confrere to replace Father Parent of Montreal who had just finished a stint of two years there. So Father Granat gathered the Canadian Solitaires around him and asked who among them was willing to go to St. Charles. As no one else was speaking up, the youngest, Father Viger, offered himself. He was accepted, and his nomination was confirmed by Father Carriere, who told him: “I am the one who is naming you.” “Since then,” Father Viger loved to say, “no one has ever asked me to stay in the United States, but no one has asked me to leave.” In fact, he was heart and soul attached to the still early work of St. Charles, and he never stopped working with all his might in contributing to its development and progress. He never forgot and never failed to quote the encouragement he had received right from the beginning in a letter from Father Rouxel, who (having seen the work at close hand) had conceived the very highest notion of it: “I congratulate you,” he wrote, “in having as your vocation to devote your life in the service of a work so evidently blessed by God; a work which, after three centuries, has at last – in a very firm, prudent, and persevering way – made real the plan drawn up by the holy Council of Trent for the classical education of candidates for priesthood.”

Written in his own hand, the list of Father Viger’s jobs shows that for the first seven years he was assigned to the teaching of Latin, Greek, – and even that early – English in the lower classes. It must be said, in effect, that on his coming to St. Charles he was involved in joining to the solid study of grammar and literature the practical knowledge he already had of English. He was thus capable, as early as 1869, to be put in charge of high-school classes of English literature and poetry, while at the same time continuing to teach Greek and French. To those he yet added Church History and the upper Religion course. As of 1882, he became Director of Our Lady’s Sodality, still remained in charge for ten years of English poetry and for a longer time of Freshman College Latin. Finally, in a letter on last October 25th to a fellow-Solitaire with whom he had always kept up a correspondence and a union of prayer, Father Viger, over seventy, thus made an account of his last functions at St. Charles: “Here I have just enough work to make my situation as pleasant as possible: three hours of Greek class and one of Elocution each week; along with that, I have charge of Our Lady’s Sodality where I give a little talk now and then and conduct the Little Office every Sunday.”

But that brief listing of Father Viger’s daily tasks is still far from giving a complete idea of what the work at St. Charles, the work of the Society, and even the wider work of Catholic education in the United States owes to him. As for Catholic education, he supplied a handbook of English literature which has become a classic in most colleges. The first edition was the work of Father Jenkins, founder of St. Charles; but for more than twenty-one years all new editions – constantly updated – were due to Father Viger with the help of his confreres. The one who probably worked most with him and had the most discussions, sometimes detailed, on the way to regard most of the technical questions, on hearing of his death, wrote: “Father Viger is the confrere to whom I am most indebted for all his advice and fraternal help. He is also one of those for whom I have always had the most admiration on account of his devotion and all the services he rendered to St. Charles.”

In the number of services let us not forget those which for more than thirty years he claimed for himself with a generosity and a remarkable affection in the domain of the infirmary. His expertise as the son of a doctor had brought him along this road and somewhat had slightly broken him in in this charitable office: by practice he acquired a growing competence, and that was all the more a benefit for the college since St. Charles was quite a distance from the city and the doctor.

In an epidemic of black fever which after the Civil War broke out in the house and claimed several victims, Father Viger organized for dealing with it a nursing service and labored at it day and night without concern for danger. Even in ordinary times, he did not go to bed without checking one last time on all the sick and without showing them some little attention with an almost maternal tenderness for each of them.

In a completely different order of things, he deserved much from the college and the Society for his painstaking and detailed studies on the history of Sulpician work in America and especially in Maryland. It was to him that Father Magnien turned in 1891 on the occasion of the centenary of the founding of the seminary to outline its history during its whole first century. In 1898, Father Viger did a like work for St. Charles on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the house. Finally, that same year, for an Illustrated History of the Church in the United States which the Bishops wanted to present to the Holy Father on the occasion of his jubilee, he was asked to do a sketch, quite lengthy and detailed of our work in the United States. The last work of our dear confrere would thus have been intended for the Vicar of Jesus Christ for whom he had from his youth conceived a very deep veneration and affection.

For some months Father Viger had been aware of a worsening of a heart ailment inherited, he said, from his father, but which for a long time had caused him no trouble. In his letter of October 25th, already mentioned, he wrote: “A more serious crisis could suddenly break the whole machine down. Who knows? I try to be always ready in so far as human weakness permits. I love to repeat the invocation: Jesu, bonitas infinita, miserere nobis [Jesus, infinite goodness, have mercy on us], and I renew my abandonment to the Blessed Virgin.” On about the same date, he informed his brother, the pastor of Epiphany parish, of his last will.

On the night of November 9/10, he underwent a crisis which did not keep him from taking up the next day his normal functions but left him quite slowed up and quite tired. On the evening of the same day, he was visited by a Baltimore confrere who was bound to him by ties of long friendship but who was unaware of the previous night’s occurrence. After a half-hour’s chat in which the past of St. Charles was the main topic, Father Viger said to his visitor: “I am glad that you came. … I am getting ready but without worry.” And the “Good evening” that he added was particularly cordial.

The next morning, Father Viger’s corridor neighbor, not hearing anything at the usual hour, entered his room to ask him how he was. He found him in bed and as if sunk in a deep sleep. He came near, took hold of the hands; they were cold and rigid. The soul of the good servant had already been gone for some time from its bodily shroud to reply to the call of the Master.

That was on the morning of November 11th. The funeral was set for the 14th, to allow time for those who wanted to, to come from long distances. The gathering of priests – nearly all former students of Father Viger’s – was very large. His brother hastened from Canada; one of his cousins, an Augustinian from Philadelphia, celebrated the funeral Mass. His Eminence, Cardinal Gibbons, braved the distance, fatigue and bad weather, consenting to be present and to give the absolution. Bishop Monaghan of Wilmington, and Bishop O’Connell, Rector of the Catholic University, were also there as was Maryland’s governor, the Honorable John Lee Carroll, grandson of the Signer of the Declaration of Independence, to whose generosity the founding of St. Charles is due.

The little college cemetery now holds a grave, precious and even venerated; but there is a gap in our ranks which obliges me to repeat the prayer whose wording came to me from Baltimore:

May God raise up workers as devoted as those he has taken from us to fill up their places and continue their work!

I recommend this intention to your prayers. And I remain always, Fathers and dear confreres,

Yours, very sincerely devoted in Our Lord.

H. Garriguet

Superior of St. Sulpice